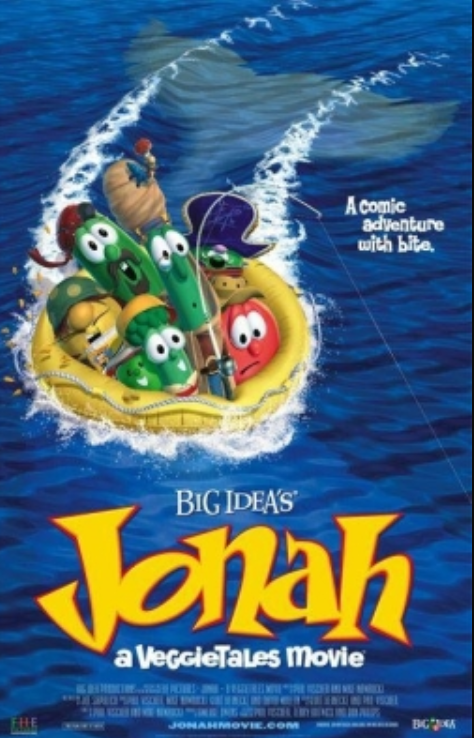

Jonah: a Veggietales Movie

This review was commissioned by @ArlequineLunaire

The Book of Jonah marks a major transition in Jewish theology. While elements of an older view of god persist in the literature after Jonah, and premonitions of the later version exist in some older stories, Jonah comes from the time in Jewish history when God was really starting to get the capital G. It's really a fascinating story, both in historical context and even at just face value.

It's also on the very short list of biblical stories that I still - even after losing my own Jewish faith, even after becoming an outspoken atheist - unironically like, with pretty much zero qualifiers.

It was therefore with mixed interest and trepidation that I sat down to watch the movie-length Veggietales movie treatment of the story. Interest because I had a mostly good impression of Veggietales from the episode I reviewed a while ago. Trepidation because there are so, so, so many ways to fuck this story up. So, how did they do?

In short, they did good. They included a lot of cool details that often get left out in children's adaptations of the Jonah story, and even went beyond that to throw in some historical connections that reflect a decent understanding of the time and place the story is set in. The humor, from beginning to end, is almost all great, with only a few sections dragging on for a bit after the joke has worn thin. The music is excellent, though none of the songs are quite the banger that "Love the Bunny" was (hilariously, there's even a self-aware admission of this by one of the characters in the movie). From the production standpoint, you can also really see how a bigger budget (apparently, the company pretty much bankrupted itself on this movie; maybe they shouldn't have gone quite so all-out after all, in retrospect...) and a few years of progress in CGI technology improved Veggitales' use of the medium since its early episodes.

But there are also a few changes they made to the story that just...I really have to ask why they decided to make them. A couple of the best and most powerful moments of the original story are lost or watered-down because of these changes, and I'm not entirely sure what the creators thought they were adding in exchange.

Hence, I say that this is a good adaptation rather than a great one. It gets the point across, and it brings a lot of new stuff to the table that enriches the biblical original, but there are also some bits that really seem like five steps forward and ten steps back.

Like the shorter Veggietales episodes, the movie has a framing narrative with a storyteller imparting biblical wisdom to a confounded vegetable in the modern day. In this case though, the framing narrative is so complicated, extended, and over-the-top that for the first few minutes I thought we were going to forgo the story-within-a-story format and just do a modern reimagining. Our familiar tomato and asparagus duo are driving a van full of rambunctious children down a back-country dirt road to some concert they all have tickets to. One little tomato girl in particular won a backstage pass as a golden ticket in some snack box, and is relentlessly waving it in front of the others' faces and teasing them about how she's getting in for free and also getting to meet the star while they aren't. Meanwhile, up front, space cadet asparagus adult is trying to keep the kids entertained instead of helping his sensible tomato pal navigate while driving. A series of events involving the tomato girl provoking the other kids, Mr. Asparagus not helping, some very badly constructed roads, a family of porcupines, and their vehicle apparently having its brakes as a button on the steering wheel instead of a footpedal for some goddamned reason results in their van off the road and down a wooded hill with two flat tires.

They end up trudging to a nearby seafood restaurant to lick their wounds and hopefully use a phone (no cell service out here, I imagine). The cucumber child who tomatogirl had been bullying most heavily is relishing the chance to hold the degree to which this is all her fault over her head. She also happened to lose her vaunted backstage pass out the van window during the hijinks, so even in the unlikely event that they don't miss the concert entirely she won't get to meet the star, which is also funny to him. Meanwhile, tomato adult is holding an understandable grudge against cucumber adult for the degree of his negligence.

It is in this state that, while waiting for the meal they ordered as they await the tow-truck, they meet the storytellers for this bible tale. And, while I was familiar with the internet meme that these guys spawned, I didn't know until just now that this movie was the origin of The Pirates Who Don't Do Anything.

Interestingly, they don't frame the Jonah story as something from the bible. Rather, they claim to have been direct participants in it. Basically, this movie takes the minor sailor characters from the Book of Jonah and kinda-sorta gives them the "Rozencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead" treatment. Only sort of. We do shift from their POV's to Jonah's at some points, which sort of puts the lie to their claim of having literally been those Iron Age sailors. On top of them, you know, still being alive.

Also, one of the pirates who don't do anything is the racist garbanzo bean from "Rach, Shack, and Benny," only he's not racist anymore! He still has the fake Mexican accent, but no ugly gold tooth, and now he's in a role that doesn't pit the POC-coded veggies against the white-coded veggies, so now he's just one more silly voice/accent among many. Good that they learned since then.

Anyway, let's get to the actual Jonah story now.

As I said in the intro, they do a pretty good job of contextualizing the story in time and space. It's First Temple era Israel, with friendly-ish neighbors to the north, an intricate Mediterranean trade network to the west, and a vast ominous continent full of vast ominous peoples to the east, all elegantly acknowledged without any awkward exposition. The Book of Jonah doesn't tell us much of anything about Jonah's social standing among his people before God sends him on his mission to Mesopotamia, but the movie decides to fill in the blanks with high status, legally recognized prophethood, and (implied) material wealth. He's introduced to us riding on a camel that makes him tower over all the other characters, wearing a priestly turban that makes him look even taller, with a stern, aristocratic demeaner and a fake posh accent.

The people are eager to hear his divine pronouncements, and happily they mostly just boil down to "keep doing what you've already been told to do." I appreciate that, despite this obviously being a Christian retelling of the story, this sequence doesn't do that thing that Christian biblical media often does where it draws a distinction between the moral commandments and the ritual commandments, with the latter being framed as contemptible distractions that miss the alleged point of the religion. The movie is true to the historical paradigm of the time, framing "don't lie, don't cheat, be kind" and "men, wear your talit" as exactly the same sort of commandment. The rabbinical categorization of commandments into ethical, practical, and ritual didn't exist yet at this time period any more than the Christian rejection of Mosaic law did. They're all just commandments, and nobody questions that.

Since I've now raised the subject, the chronological placement of the story actually runs into an interesting conundrum with adapting the Book of Jonah. Like the previous Veggietale I looked at, this story falls into that weird alt-history genre that has a historical oppressor of the Jews undergo a divinely inspired change of heart and end up not doing the oppression. The tricky thing about it in this case is that Jonah is set before the Neo-Assyrian invasion, but it was written afterward. The reader is expected to have a visceral hatred for the Mesopotamian empires by default, but the events that caused that presumed hatred haven't yet happened in the story (or at least, have only just barely started to happen), and the events of the story as written would have caused most of them to NOT happen if they'd actually taken place. Adapting Jonah for a modern, primarily non-Jewish audience is thus a complicated task, and the movie...mooooostly does it okay? I think?

What we're shown of Israel looks like a prosperous fantasy kingdom of vegetable people. Everyone seems to be well-dressed and healthy. Economy is thriving. Architecture is a lot more impressive than it really would have been historically. These people aren't really portrayed as having much to be mad at anyone about.

Meanwhile, the evil of the Assyrians (portrayed as butternut squashes with a prevalent pea minority who live in a Mordor-esque wasteland citadel) is characterized as them having a cultural penchant for lying, stealing, and hitting people in the head with rotten fish.

They're not shown to be a threat, or an oppressor, or even really much of a hazard. Unless you go marching into their homeland looking for trouble, they're just...kind of annoying.

So, when Jonah receives his divine commandment to go to the Assyrian capital city of Nineveh and warn them to repent before they face destruction for their evil ways, and has his disgusted reaction at the prospect of ever going there - let alone on an errand of mercy - the nature and strength of Jonah's convictions can't really land, and we can't sympathize with him, let alone understand why we might be tempted to behave similarly. His generally haughty, privileged demeanour only compounds this.

Like I said, this would be a tricky problem for any adaptation of the Book of Jonah to solve. It was never going to be perfect. Veggietales' approach to it drops the ball by softening Nineveh, haughtifying Jonah, and ignoring the extent of the (justified) resentment between Israelites and Assyrians like this, though.

That said, there's also something that the story does *extremely right* in this sequence, and it involves a piece of subtext that children's Jonah adaptations often miss.

In the musical number where Jonah refuses the call to adventure, one of the refrains his song comes back to is "No, it cannot be; thy messages are meant for me and my brothers."

It's not just that he hates the Assyrians. It's also that God offering judgement and salvation to a different people - and not even one of the closely related next door neighbors like the Edomites or the Nabateans or the Phoenicians, we're talking way off on the far end of the Semitic world - takes away from Israelite specialness. This is an aspect of the Jonah story that Veggietales doesn't drop the ball on, and which a lot of other retellings do. So, points for that.

Jonah meets the Pirates Who Don't Do Anything at Jaffa port, and pays for passage overseas to Tarshish, in the opposite direction from Nineveh in defiance of his divine mission.

Looks like Veggietales has gone with the "Tarshish refers to Tartessos" interpretation. Nowadays I believe the academic consensus is that Tarshis is actually New Tyre, aka Carthage, on the opposite coast, but I don't know if that was the case back in 2002. Just a minor quibble, not a big deal either way.

A much more major quibble comes shortly after this, when the Pirates Who Don't Do Anything and their passenger are beset by a mighty storm.

In the biblical story, the sailors realize that such a storm could only be the result of divine anger. They all pray to their own gods (like most merchant crews on the ancient Mediterranean, these sailors were an eclectic group from many different lands), but none of their prayers are answered. They decide that someone onboard must have really offended the gods, and since they haven't maimed any cyclopes recently it's probably just one person with one hidden transgression. Jonah comes forward (in the movie, they divine the culprit using Go Fish cards before he finally confesses, which is adorable and hilarious) and tells them that he knows he is the one who angered his god, and that they should throw him overboard to be spared his punishment. The sailors refuse, insisting that with enough prayer and repentance on one hand and enough maritime skill on the other they can get through without anyone dying. But, the storm only gets worse, and Jonah only gets more insistent, so with heavy hearts they finally let him drown himself.

This is a remarkable scene in the context of the Hebrew bible. While non-Jews are sometimes portrayed positively, they are virtually never portrayed positively in close proximity to their own religious practices. This scene breaks that rule. The sailors pray to their foreign gods *and also* are horrified by the notion of letting a passenger drown.

In this movie, they're eager to toss Jonah overboard the instant that he tells them that it would end the storm.

They do try to rescue him again after the storm instantly dies down, but only because they think Jonah's god might be satisfied now and thus the danger might not return.

-___-

The PWDDA are a great trio of morally ambiguous bozos. They're funny. They're watchable. But putting them here just....eeeeeeeerghhhh.

Jonah gets swallowed by the whale, and there's a slapstick chase scene that's fun enough but goes on a bit too long and feels filler-y until eventually the whale gets away. It should be noted here that the ship had one other passenger besides Jonah; an itinerant carpet-dealing caterpillar by the name of Khalil. Khalil is...honestly, he's kind of a fake-Persian-accented version of Hooty, from "Owl House." Clingy, needy, way too friendly, always trying to involve himself even when he knows he can't actually help with the situation, etc.

Anyway, the shenanigans result in him ending up inside the whale along with Jonah (the whale's belly is full of old shipwrecks, because Disney lol). And is in there keeping him company and trying to cheer him up about their situation when Jonah - who had been resigning himself to a well-deserved death - gets visited by angels who give him a blues-y number telling him to stop being such a prick.

If God is willing to forgive the Assyrians if they repent, then is it really beneath Jonah to do the same thing and get the same mercy?

This visit from the angels is original to the movie. In the book, Jonah came to this conclusion on his own. But hey, it's more dramatic this way, and I don't think it loses anything by doing this.

Anyway, the whale spits him and the caterpillar out, and they undertake the long overland journey to Nineveh. Kudos to the movie for remembering how landlocked the Assyrian heartland was, a lot of adaptations forget that. And, here there's another weird thing involving the PWDDA that has me kind of scratching my head. They did have to expand the sailors' role, given that they're the ones telling the story, but this...it creates issues.

Apparently, the PWDDA have won a golden ticket sweepstake in a snack box (lmao) that earned them a cushy place to live in Nineveh, by total coincidence. They help Jonah enter the city passed the suspicious guards, but then...get arrested for stealing more snack boxes. And Jonah gets arrested with them. And they're all going to be executed via giant descending fish-statues aimed at their heads.

Now, I think I get why the creators did this. In the original story, the Assyrians repent and change their ways pretty much as soon as Jonah delivers his warning, in a way that feels much too easy. This arrest and near-execution feels more like the sort of thing that *should* happen at Jonah's destination, and it's also a chance to show the audience how brutal the Assyrians are instead of just comically obnoxious with the wanton fish-slapping.

But, on the other hand, the fact that the PWDDA came into Nineveh and then committed an actual crime (even if it's a silly crime that shouldn't merit death) sort of muddies the waters. It also makes Jonah's peril here irrelevant to himself, his mission, or even the broader politics surrounding Assyria and Israel. So, I think this plot point could have used a little refinement. Having something *like* it serves the story well, but it needed more fine-tuning.

As for the resolution of this situation...I can't decide if this is a work of absolute genius, or another case of horribly missing the point.

So, historically, the Assyrians had a fish-god motif that they used a lot. Veggietales keeps that in, and ties it in with the derpy slap-people-in-the-head-with-rotten-fish tradition it invented. When Jonah is about to be executed, he babbles out the story of how and why he came to Nineveh, and when he gets to the part about a giant sea creature swallowing him the Assyrians all start paying attention. They have a sharp-nosed priest sniff for the whale-gut stench on him (erm...apparently he didn't wash himself in the entire trip to Nineveh from the coast? lol), and when its presence is confirmed they recognize Jonah as a messenger of their god rather than just a Levantine one they don't care about. Therefore, they hear him out and take his message seriously.

...

There's a LOT going on with this addition. Some of it awesome, some of it I'm less sure about.

First, to pre-empt any questions about this: the Book of Jonah describes the creature that swallowed him as "a great fish." As far as anyone knows, ancient Hebrew didn't have a separate word for "whale" (whales existed in the Mediterranean, but the Israelites classified them as type of fish rather than a different animal). So, the "great fish" of Jonah could have been a whale, or it could have been a shark, or it could have been the mythical Leviathan himself. Depicting it as a whale has become somewhat traditional, and since we don't really know what the original author had in mind it isn't technically incorrect.

That said, it is possible (and even likely) that Jonah's author was gesturing at the Assyrian fish motif with this story beat. Having Jonah fall into the abyssal depths inside of a fish, but then being returned to the surface when he earnestly cried out for forgiveness and vowed to do as God commanded him, basically foreshadows the redemption of the fish-totemed Assyrians. The connection IS there in the source material, and I think it was clever for the Veggietales crew to capitalize on it.

But, doing it like this changes the message of the story. Now, it's only *because* Jonah disobeyed God and tried to run that he was able to do the job in the end; if he'd gone straight to Nineveh without getting swallowed first, they wouldn't have given him the time of day. The Assyrians were a little too easy to redeem in the original, sure, but this approach to complicating it muddles things in a weird way.

I wonder if this might just be the creators' Christian sensibilities at work. The idea of a sinner who needs to commit a sin in order for redemption for everyone to happen later is a thing in Christianity. To me, it's just kind of a "say what now?" especially in light of the original story's ending. Which...well, I'll get to that now.

...

After the Assyrians treat Jonah's new commandments on how to behave as a message from their own god and start praying for forgiveness, Jonah leaves Nineveh and situates himself on an overlooking hill. Close enough to see the fireworks when God doesn't accept their pleas, and far enough to be outside of the blast radius.

And, this is where the importance of Khalil the annoying caterpillar reveals itself. Another oft-missed detail of the Jonah story is that when God causes a fast-growing plant to spring up and give Jonah shade while he watches Nineveh, it is the actions of a "worm" that cause it to quickly wither again.

It turns out that the sailors aren't the only characters to get the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead treatment.

Jonah thinks the plant was created to give him shade, for the sun is hurting him. Khalil thinks it was created to give him food, for he is hungry. When Jonah berates him for it, and even deigns to look down on him for it, Khalil's good nature gives out and he calls Jonah out for caring more about a plant than he does about the thousands of people below AND THEN HAVING THE AUDACITY to call himself a better person than Khalil. Why does he think he matters more to God than everyone else does?

Worms are actually a recurring symbol in the Hebrew scriptures. Often serving as divine messengers of humility, specifically. So, it's appropriate that they have Jonah's final verbal call-out come from the very worm that ate the plant.

But, this is also followed by the most glaring omission of the entire film. See, the story-within-a-story ends here, with Jonah left alone and it being unclear if he will finally abandon his self-righteousness and truly repent like the Assyrians have, or if he would rather die in the desert with his pride and aggrievement intact. With that question left hanging, we go back to the framing narrative, and the question of whether or not the tomato girl and the asparagus dad will be forgiven by their peers.

...

While Khalil does communicate some of the spirit of the omitted divine revelation, it's just nowhere near as profound as this:

“But God said to Jonah, “Is it right for you to be angry about the plant?”

”It is,” he said. “And I’m so angry I wish I were dead.”

But the Lord said, “You have been concerned about this plant, though you did not tend it or make it grow. It sprang up overnight and died overnight. And should I not have concern for the great city of Nineveh, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand people who cannot tell their right hand from their left—and also many animals?””

The implications of this passage are an absolute rugpull for God's portrayal throughout the scriptures.

First of all, you cannot convince me that this is the same entity who wiped out all of humanity besides a single family in Bereshit/Genesis. Let alone the one who was so determined that the Egyptians should endure their full predetermined punishment in Shemot/Exodus that he took away Pharoah's ability to repent.

Second, the way God talks about the city of Nineveh here, implying that it is akin to a plant that he has tended and watered like a loving gardener and that it would grieve him to have to uproot, is unprecedented in the scriptures. It's all but explicitly saying that every nation is God's nation, every city is God's city, with the Israelites only differing from the others by being *aware* of that fact. There's lip service paid to this kind of universality of god in the preceding books, but I never feel like he comes close to putting his money where his mouth is until Jonah.

In light of this, even the anticlimactic ease with which the Assyrians are made to repent and reform could be meaningful. No reason is given for why Jonah should have to travel all the way from Israel to relay the warning to Nineveh, when God could have just chosen a messenger who was already nearby. The story can be interpreted as God already knowing that the Assyrians were going to redeem themselves, and the entire thing being intended as a lesson for Jonah all along. I'm not saying I favor that interpretation, exactly, but it's a valid one.

Telling someone else to forgive their own oppressor is generally a bad look. This story makes it different, though, in large part because the final words are coming directly from God and not through a mortal messenger. It's not saying to judge or to expect victims for refusing to forgive their victimizers; it's saying that if you are a victim, you should be willing to forgive your victimizer if they genuinely change. Like, as an ideal to aspire to, that's what the story is advocating.

Along with a reminder that wallowing in self-pity and resentment can cause one to descend into the very pit that the oppressors hail from. A warning that modern Jews really, really, really need to start thinking about.

The Veggietales movie conveys some of this. Just...it falls painfully short of conveying all of it. This - along with the related issues concerning the portrayal of the sailors' behavior - is by far my biggest criticism of this film.

...

Predictably, the denuement has the vegetables all forgiving each other, giving happy endings to each of their personal Jonahs. It works well enough for the tomato girl being forgiven by asparagus boy, but I have to raise my eyebrow at how it applies to the grudge between their fathers. See, the crux of Tomato Dad's spat with Asparagus Dad was specifically that he doesn't want to drive anywhere with him after this. Which, in context, isn't really an act of spite or contempt or even really a denunciation; it's just an acknowledgement that Asparagus Dad is a bad navigator and can't be relied on to help with road trips unless that changes. It's not a matter of forgiveness, but of faith. A sincere apology isn't what fixes this, an improvement in roadtrip skills is.

Equating these two types of "forgiveness" is...honestly kind of a hazardous message for kids, I think. It kinda seems like it's telling them to "forgive" their clumsy friends by letting them handle the delicate glass objects again, you know?

Fortunately, the greater focus of the movie is on the children. And that side of the applied moral works just fine.

...

On a random note, while Tomato Dad and Asparagus Dad mention their wives once or twice, I swear to god they're written like a gay couple raising these kids together. It's not just me, right?

...

Final ending has the singer they wanted to make the concert of ALSO having road trouble and ending up stopping at the restaurant, so they all meet him and get to hang out with him until the tow truck arrives. Providence!

So, I give this movie a B+. It's fun, it's clever, it moooostly gets the point across, but that just makes its handful of serious missteps stand out that much more. Jonah is a hard story to adapt, and again, Veggietales did better than most.

It's just a pity that the production of it basically ruined the company.