Scrooge McDuck "Tralla-La"

This review was fast lane commissioned by Aris Kataris

Another of the Scrooge McDuck comics by Carl Barks, this one published a year after "Back to the Klondike." Like many of the early Scrooge stories, this one is a commentary on wealth and greed that...well...even moreso than "Back to the Klondike," this comic seems a little backhanded in what it's trying to say. If it knows what it's trying to say at all.

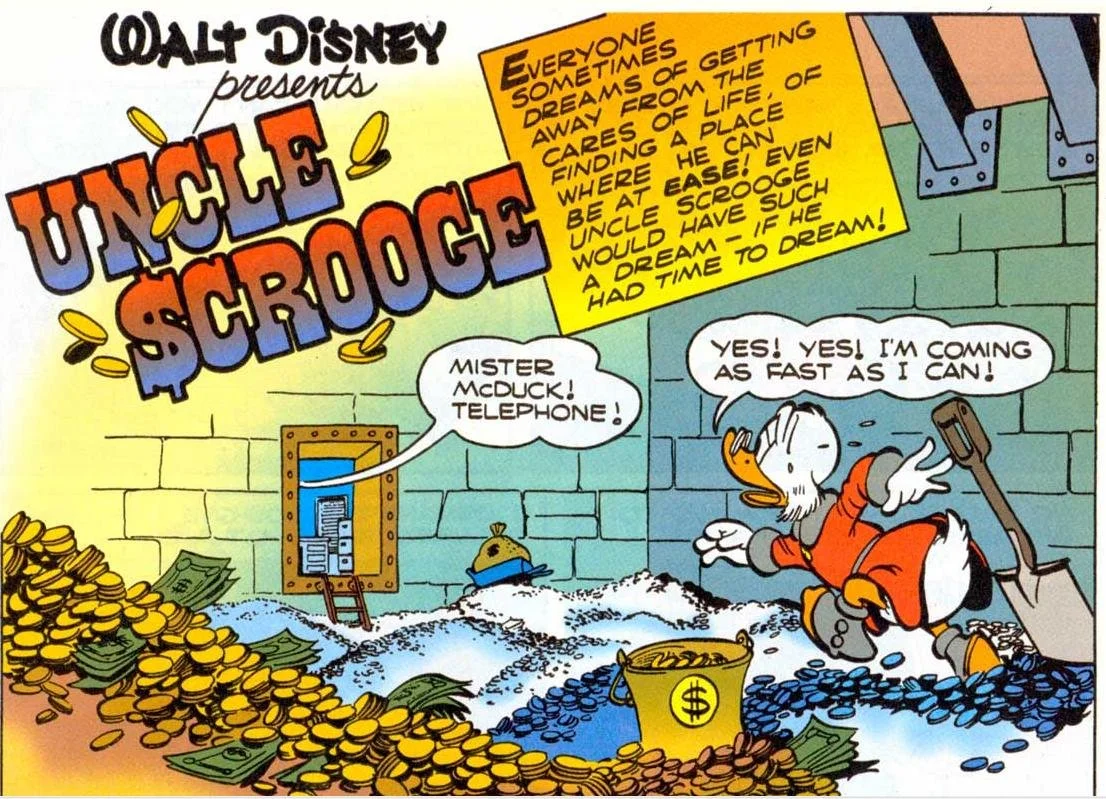

We open on the Vault of Yre, where the black king of that place is feeling his nerves start to give out as the wheel presses relentlessly in on him.

Turns out the call is from the dictator of the sowbug nation, who is demanding another gold-filigreed limousine in exchange for not nationalizing Scrooge's oil fields. Scrooge knows the CIA will just give him a Look if he goes to them over one measly limo, so he's forced to give in once again. Neocolonialism is so exhausting. Scrooge misses the good old days of normal colonialism, I'm sure.

This call is followed by a cacophony of other calls and visits, from lobby groups demanding his yearly dues, to society clubs asking for contributions, to charities threatening to release the swarms of homeless they're trying to feed onto his property unless he pays them off, to parents begging him to give their children life advice, to communists making attempts on his life. I'm not even joking about that last one.

We never find out what he's under investigation by the federal government for either.

The chains of wealth pull at Scrooge harder and harder, no matter how hard he tries to kick them off and run from them, to the point where he has a psychotic break and tries to become a squirrel. The logic being that squirrels don't have a concept of money, and are happier for it. To be clear, these are actual, small animal squirrels, not anthro-squirrel people living in the same society with the ducks and mice and suchlike.

...you know, I think it might be intentionally telling that even in his desperation to escape the rigours of wealth, Scrooge is still latching onto an animal best known for its hoarding tendencies. Fantasizing about being a butterfly or a sparrow or something is still beyond his imagination.

After his longsuffering nephew wrangles him to a doctor who prescribes him some powerful nerve medicine, Scrooge returns to coherence. He still starts having nerve symptoms whenever the topic of money comes up, though, so he still wants to find a way to escape from it. Or, well, sort of. The shaking starts up whenever the topic of him spending money comes up, specifically. This is reiterated over and over again throughout the adventure.

Scrooge thinks that he's having a change of heart. That this is the accumulated stresses of his managerial owner life finally making him regret living it. Really, though, it's just an intensification of his preexisting habits. He's not getting tired of being rich, his cheapness is just starting to have neurological symptoms in addition to the behavioral symptoms.

The comic seems to be aware of this. The characters aren't, though, and they never seem to come close to that awareness. Which is one of several things that makes the ending of this one a bit frustrating for me.

While trying to decide how to get rid of his wealth without having to get rid of any of his money, Scrooge stumbles across the legend of "Tralla-la." An isolated valley, lost somewhere among the cloudy peaks of the Himalayas, where the people live in abundance and comfort without any concept of wealth or ownership. Scrooge sets out to find it, reluctantly (with the help of his nerve medicine) paying for aircraft to do the searching.

...

Scrooge sure does get proscribed an awful lot of different medications in these 1950's comics, doesn't he?

...

Scrooge and his nephew and grandnephews (who keep asking him about paying them for all this personal assistance, only for him to have panic attacks and dive for his medication) end up parachuting down into the narrow valley that they hope is Tralla-la. And...they're in luck. Sort of. Ish.

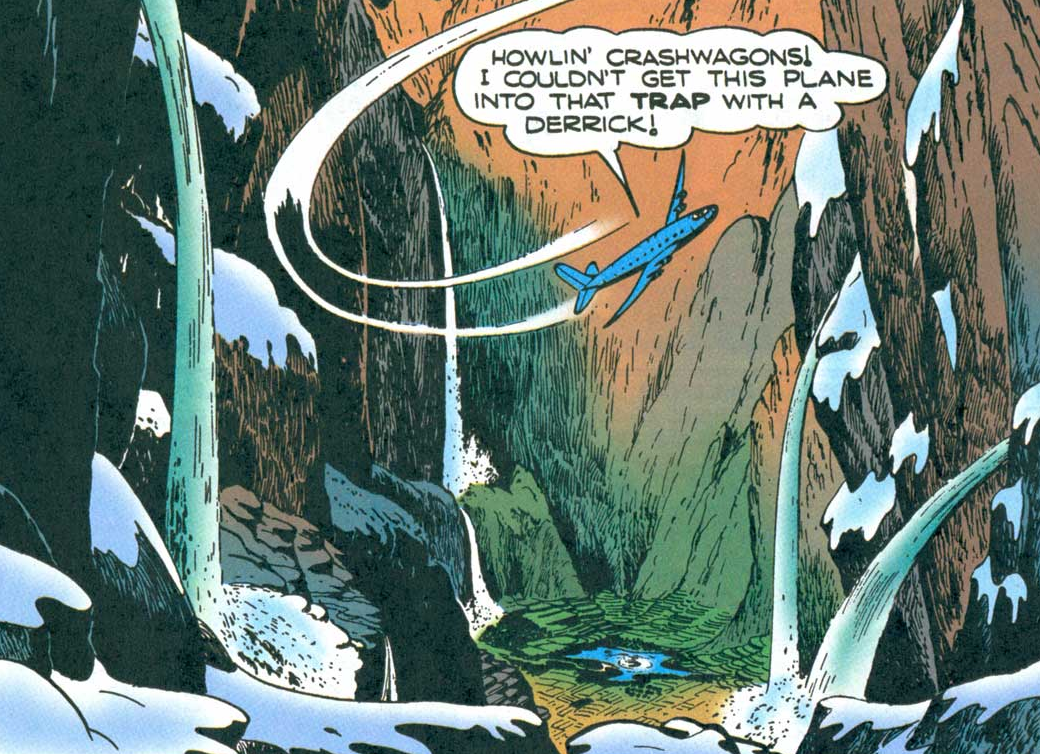

Before that though, there's some remarkably good art in this sequence, for what it is:

Looking at this panel out of context, I'd never have guessed this was a Scrooge comic. Even moreso than the other such panels I said that about in the last Scrooge comic I reviewed.

So, after having a close call with the big whirlpool in the central lake, the ducks climb ashore and meet the natives. The handwave for how Scrooge is able to talk to this uncontacted tribe is amusing in its sheer handwave-y-ness.

Lol, sure, fine, whatever.

Anyway, true to the legend, the Tralla-laites have no concept of money, and are a generous and community-minded people. They proactively gather the supplies that Scrooge's family dropped out of the plane in advance of themselves and return it all to the visitors. Food is shared freely. Lodging, likewise, freely granted. When Scrooge says he wants to move here permanently, they cheerfully allow him to start building a house for himself in their village and accept him into the community.

But...well...they aren't actually quite what Scrooge thought they were.

And...here's where I'm really of two minds about this story and what it might be trying to do.

...

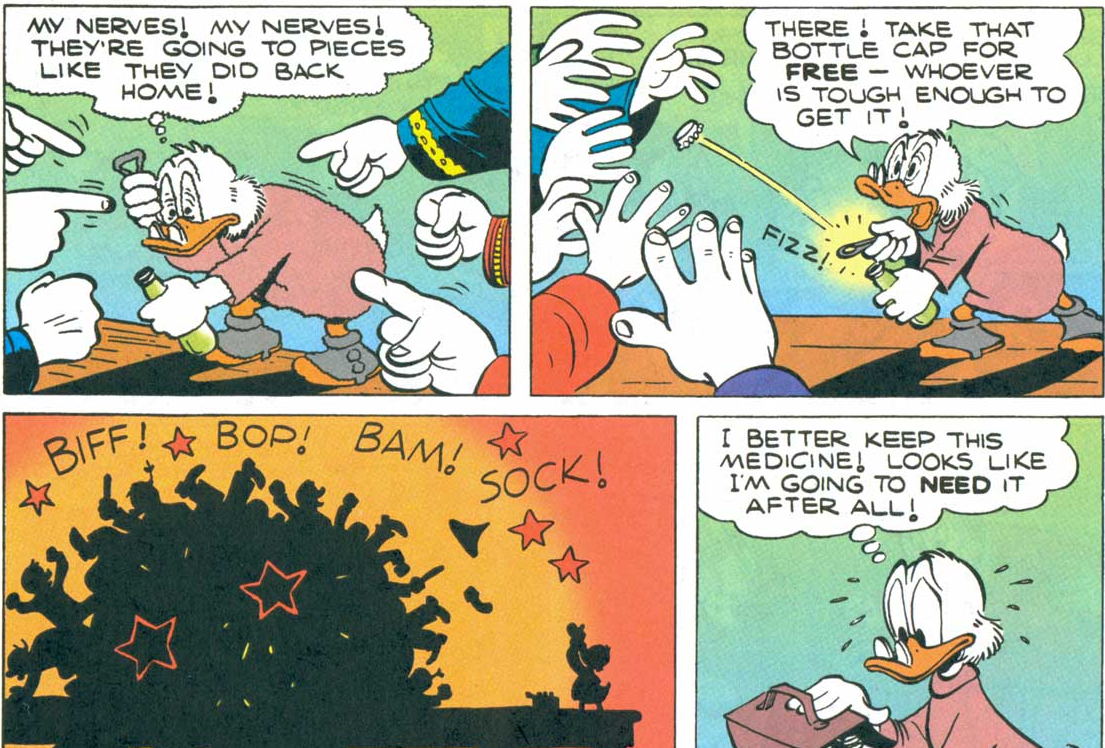

So, on its surface, what comes next is a pretty elementary satire of how greed corrupts and reshapes every society it comes in contact with. Scrooge throws away one of the bottlecaps for his medicine (it comes in basically beer bottles, apparently. lol) and one of the natives picks it up. And then all the other natives want it from him, since it's the only bottlecap in the entirety of Tralla-la. It gets traded and accumulates value. And then they find out that Scrooge still has several bottles of his medicine with him, and that each of those bottles has another cap on it, and suddenly he's the rich man being beseeched and wheedled and threatened by the rest of the community again.

In an effort to undo the damage that he's caused to this idyllic society, Scrooge sends Donald out of the valley with a blank check to have airplanes drops millions of bottlecaps over the valley and remove the disruptive scarcity of this new commodity, only he miscalculates the amount and nearly wipes out Tralla-la society by literally burying them in bottlecaps. And then there's a whole fiasco about saving them from being literally crushed under the weight of their newfound greed, before Scrooge and Co return home with Scrooge still having panic attacks whenever anyone asks him for money.

...

Before getting into this, yes, I *know* that I'm overthinking this comic. It's not supposed to be dissected at the level I'm about to dissect it at. My hope is that when I'm done with my dissection, you'll agree that the author underthought this story when he decided to tell it the way that he did.

Also before getting into it, I want to make it clear that I do understand that the comic is not approving of Scrooge's behavior. Obviously, the joke about Scrooge thinking he needs to fly away to the Himalayas to get away from his wealth (while meanwhile anyone raising the subject of him just giving it away is met with literal nervous breakdowns) is intended by the author. That's Scrooge being dumb and greedy, and you're supposed to laugh at him for it. I'm not criticizing its assessment of the individual characters here, but rather it's background assumptions about society.

Okay. So.

The idea that flashing money in front of an idyllic greedless villager can instantly infect him like a meme-virus and cause him and his neighbors to develop the entire system of capitalism from the ground up in the course of days IS funny. I'll give it that. There's also, as I said before, some more serious commentary to be gleaned about the toxic effects of capital on traditional societies when they're exposed to outside pressures. But. There's ALSO a lot in this comic that seems to want to be a commentary on human nature itself, and here is where I start to have problems.

First, let's look at how the Tralla-la society is portrayed. Initially, we see them do some generally selfless and generous acts, but we never get into how their society actually works. How distribution happens. How labor is allocated. Etc. But, when the first bottlecap gets into the hands of the first native, we get some very telling panels.

Before Scrooge had any impact on Tralla-la society at all, families apparently owned sheep. Not the village or the tribe as a whole. Individual families. They had a concept of sheep being "mine" or "yours" rather than "ours."

Even if we assume that all the developments that follow from this point - the bartering process, the rising sheep-value of the bottlecap as it's traded, the idea of trading labor for currency that someone offers to do a few panels later, etc - all sprang fully-formed from the natives' minds after Scrooge gave them the bottlecap, the fundamental axiom of private property was already there. And everything else follows logically from that, with or without bottlecaps.

The legends were wrong. They already had a concept of wealth. If they didn't, the bottlecap wouldn't have had anything to work on.

They also have laws. With criminals being sentenced to proscribed punishments for breaking said laws, by a court. It's treated as a throwaway gag in the comic, but it's in there.

Now, I inferred at the beginning that part of the point of this comic is that Scrooge literally can't imagine a world without greed even when he tries to. If he could be any animal, he'd be a squirrel stashing nuts. When the psychological toll of hoarding his wealth becomes too great, he develops a condition that makes him hoard it even harder. Etc. Through that lens, treating this all as just a character study of Scrooge McDuck, Tralla-la being another dead end for Scrooge's personal development does work.

If we're talking about human nature as a whole, though, then um.

Isolated, low-tech societies without private property actually exist?

They're a critically endangered species, but they were less critically endangered in the 1950's when this comic was written than they are today.

The idea that the closest you could ever come to a truly economically equal society is "lol barter" is completely untrue. It was even more obviously untrue during the author's time than it is in our own.

...

The introduction of currency into a barter economy does allow for more rapid accumulation and reproduction of wealth. But it doesn't enable the accumulation and reproduction altogether. Money is a tool invented to do a job that was already in demand. Poverty and wealth had to exist first in order for currency to make any kind of sense.

What we see in this comic is sort of a...fetishistic demonization of currency as the bringer of greed. Casting the blame in exactly the wrong place. It wants to think that there's a mode of human society that wasn't greedy and competitive, but it can't imagine a human society that actually isn't greedy and competitive, and struggles when trying to portray one. It knows that *something* has historically worked to turn more egalitarian societies into less egalitarian ones, but for want of an understanding of what that could have been it just shrugs and points to money.

...

Shangri-la is an invention of twentieth century British-American author James Hilton. Hilton never actually went to Tibet. According to his own statements, he never even interviewed any Tibetans. His cultural studies for the "Lost Horizons" novel consisted of perusing artifacts at the British Museum and reading the travelogues of European explorers who had been there. At best, his concept of Shangri-la is loosely inspired by Mahayana Buddhist legends about hidden earthly refuges. From the beginning, Shangri-la was the creation of a white guy from an educated, capitalist background testing the limits of his imagination against the mountains of the mysterious orient.

If this comic had been written more recently, I might think that the author was commenting on that at well. That Tralla-la is just another sad fantasy of Scrooge's, flawed the way that all his fantasies are flawed, because he simply cannot imagine living without wealth. He went out to the Himalayas in search of nothing but himself, and so himself was all that he could find there.

I don't think that the author was thinking along those lines, though.

I think that this comic is no more capable of imagining a world without ownership and greed than its main character is.

I think that it believes its own limitations to be universal ones. I think that it wants to be telling a tragedy-wrapped-in-cartoon-comedy about the inescapability of avarice, but the real tragedy here is that it believes its own insidious lie.

Maybe I'm wrong. Maybe the author was much more self-aware than I'm giving him credit for, and this comic really was meant to all be internal to Scrooge and a commentary on his blinkered worldview. But, I think that it's much more likely that Scrooge the comic suffers - albeit less acutely and for much more well-meaning reasons - in the same mind prison that Scrooge the character does.